Introduction

On Feb 11 2013, Dr Len Almond came to the university to talk to our students about TGfU, the original ideas that informed the approach, and where he felt we should be going in the future. It was a very stimulating talk, and I’ve tried to summarise what were, to me, the main points below.

- We need to develop young people who truly understand the nature of games;

- We need to develop players with game intelligence;

- We need to help players appreciate the translation of knowledge in games (i.e. when, how and why to use techniques and tactical principles);

- We need to develop games players who are playful and confident to experiment at will;

- Good games players need to have tactical understanding AND technical prowess (i.e. what is tactically desirable must be technically possible – Alan Launder in Play Practice);

- In order to achieve this, we need to start by teaching children in very basic game forms…

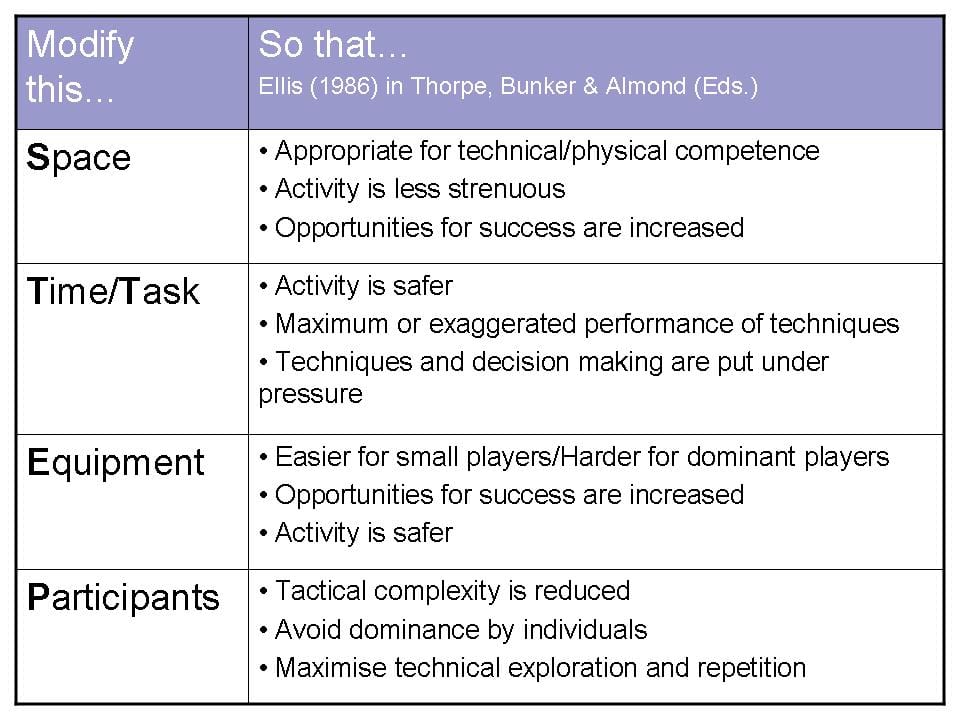

The final point is of vital importance since it is something very few teachers and coaches currently do. Creating developmentally appropriate game forms often means:

> Reducing tactical complexity to make decision making easier (before gradually increasing it);

> Increasing opportunities for success (and therefore building confidence);

> Focusing on a much smaller range of possible techniques than is normal.

This challenge – of creating units of work around very basic game forms – therefore presented the impetus for three weeks of practical work from the students who were given the following practical task:

Create a 6-week unit of work for complete beginners in one of the four game forms drawing on the pedagogical principles of exaggeration, representation, tactical complexity and sampling.

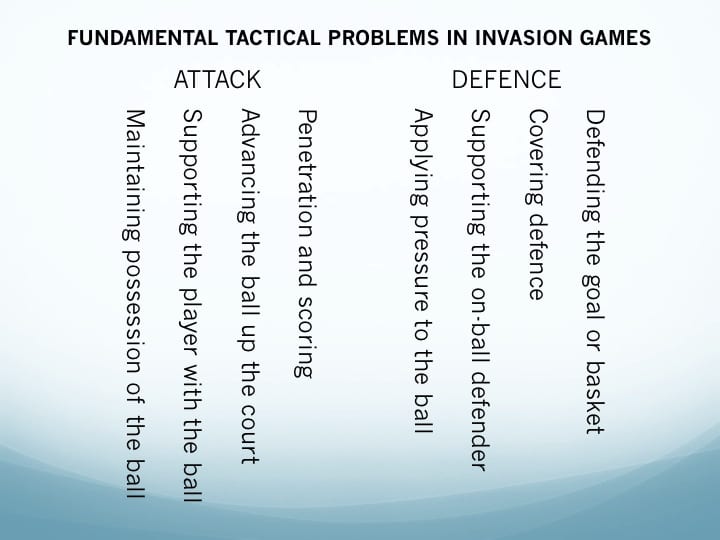

In order to assist them in their task, the students were given a map of the basic tactical principles involved in each sport form along with a slide to suggest ways in which they might modify their games to using the pedagogical principles (see below).

Below I have summarised the output under the headings of the game forms. I include the unit plans developed by each group and some videos of selected games they decided to demonstrate.

Target games

The group decided to have a indoor golf-themed unit of work, and devised the following games. Some example videos show how two of the games might work.

| Week | Tactical principle | Game |

| 1 | Hand-eye coordination | Throwing to targets |

| 2 | Stance and footwork | Lilly pad putting |

| 3 | Calculating distances | Cliff hanger |

| 4 | Choosing a target | River crossing |

| 5 | Risk-reward calculations | Bunker buster |

| 6 | Culmination of weeks 1-5 | Create your own mini-golf course |

Net/wall games

This group decided to have a tennis-themed unit of work, and devised the following games. Some example videos show how two of the games might work.

| Week | Tactical principle | Game |

| 1 | Appreciating court length | Long and thin |

| 2 | Appreciating court width | Short and fat |

| 3 | Using court length with racket | Length and accuracy |

| 4 | Using court width with racket | Width and accuracy |

| 5 | Stroke accuracy | Full court game with targets |

| 6 | Culmination of weeks 1-5 | Full court game with higher net |

Striking/fielding games

This group decided to have a baseball-themed unit of work, and devised the following games. The example videos show how two of the games might work.

| Week | Tactical principle | Game |

| 1 | Short fielding | Strike out |

| 2 | Long fielding | Wall catch |

| 3 | Base running | Running rings |

| 4 | Hitting for accuracy | Hand squash trios |

| 5 | Hitting for power and accuracy | Multi(base)ball |

| 6 | Culmination of 1-5 | Rainbow baseball |

Invasion games

This group decided to have a netball-themed unit of work, and devised the following games. The example videos show how two of the games might work.

| Week | Tactical principle | Game |

| 1 | Maintaining possession (simple) | Keep the ball |

| 2 | Maintaining possession (and advancing the ball in areas) | Four corners |

| 3 | Maintaining possession (against defense) | Four corners (overload) 5v3 |

| 4 | Appling pressure to the ball | Four corners 4v3 (or 4v4) |

| 5 | Positional play | Passing sequences |

| 6 | Appling basic netball rules | High-5 netball |

Summary

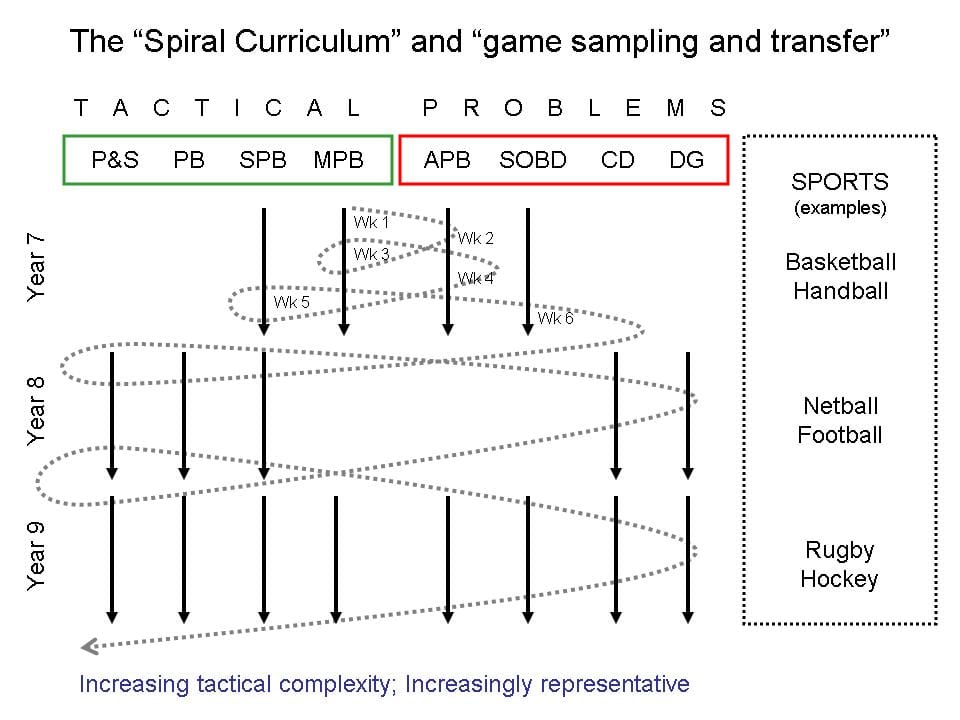

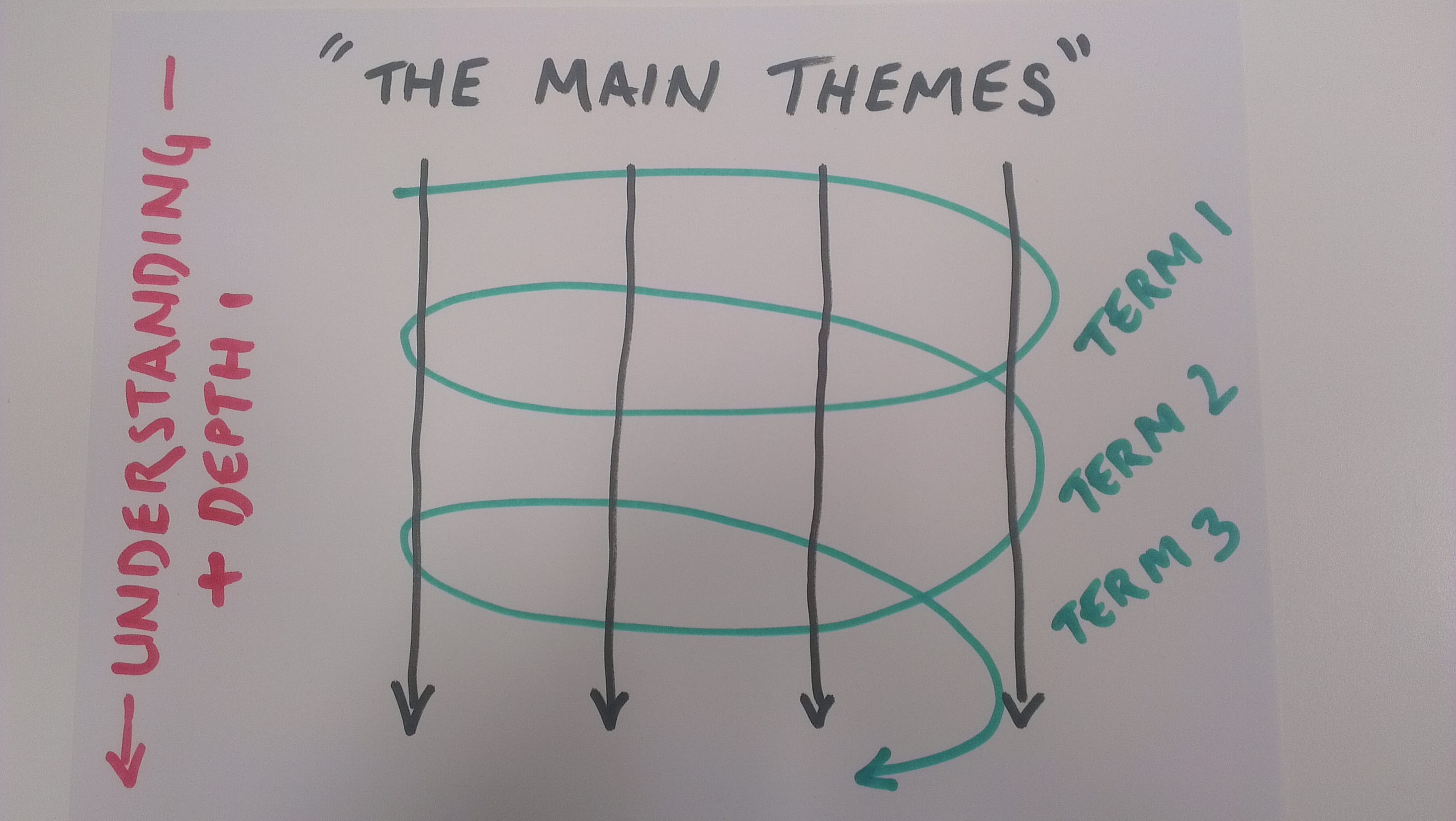

I also asked that the students to think ahead, into the following few years, to suggest how they might draw on Bruner’s notion of the spiral curriculum to develop a longer-term series of units that, over time, would form a whole school PE curriculum. By way of example, I’ve created an outline for invasion games PE curriculum over three years, below.

The students drew on two main resources for inspiration in developing their units. First, the original text by Thorpe, Bunker and Almond from 1986 that contains example units of work for basketball and tennis; and second, Mitchell, Oslin and Griffin’s 2005 text on Teaching Sports Concepts and Skills.

However, most of their games are original and they tried hard to show how each game met the requirements we’d set out for simple game forms (reduced tactical complexity, more opportunities for success, focus on a small set of techniques). Of course, we’ll never really know if the unit plans are effective until we try them out in schools, but I hope that, if Len were to have seen our games, he’d be satisfied that we were moving in the right direction. That is to say, I hope we’ve been able to capture the original intentions and spirit of the TGfU movement in our short experiment.