Some years ago, I recall a student explaining to me about how important he thought “tempo” was to a coaching session. He was doing his FA level 3 at the time and was reflecting on the value of ‘pace’ and ‘connectedness’ in a coaching session. I agreed with him and immediately began to think about what this would mean in practical terms. Since then, I’ve been searching for a metaphor to illustrate the value and nature of tempo in a coaching session and I think I’ve finally hit on one that works.

The DJ metaphor

For a time in her 20s my sister was a professional DJ, jobbing around nightclubs in Leeds. I therefore have a little bit of inside knowledge about how DJs operate. For the purpose of the metaphor, I think it’s possible to summarise a few golden rules every DJ (and, by analogy, every coach or teacher) would want follow in their work:

For a time in her 20s my sister was a professional DJ, jobbing around nightclubs in Leeds. I therefore have a little bit of inside knowledge about how DJs operate. For the purpose of the metaphor, I think it’s possible to summarise a few golden rules every DJ (and, by analogy, every coach or teacher) would want follow in their work:

- Connections between tracks should be almost imperceptible to the audience;

- Always stay in touch with current trends, and try to mix classics with the current and future floor-fillers;

- Build an atmosphere and keep the audience excited about what’s coming next.

We can all think of times where a DJ has failed to do these things: when they’ve messed-up a mix to the jeers of the dance floor; when they’ve played a corny track at the wrong time; when they’ve followed-up a floor-filler with a floor-killer; or, at worst, when they’ve lost the plot altogether and left a period of silence or dead air (the classic wedding DJ error). Equally, I recall nights where the DJ got everything right: engaging a club of thousands of people in hours of seamless, flowing music and dancing, linking classics with contemporary favorites in imaginative and interesting ways. This takes great skill and knowledge, of course, with days or months of preparation coupled with the ability to read the crowd and to react to the ‘vibe’ of any given situation. The same could be said of teaching and coaching, I think, though our jobs are made more difficult by the fact that we need to link together whole series of sessions, often over months of even years.

Why is tempo important?

Since the 1970s, researchers in PE have shown that time is a critical variable in learning. Indeed, the concept of Active Learning Time (ALT), which incorporates time spent engaged in motor tasks (e.g. practicing skills and playing games), non-motor learning tasks (e.g. answering questions), and supporting others in learning (e.g. peer tutoring), has been shown to be directly related to achievement (Van der Mars, 2006). Maximising ALT is therefore important in two respects: first, in a simple sense, more ALT (or ‘time on task’) means more practice time; and second, by reducing time spent inactive, the teacher or coach reduces opportunities for disruptive behaviour. As Lawrence and Whitehead (2010) explain, the more time participants spend inactive the more likely they are to be disruptive; and more disruption requires time to be spent directly managing behaviour, which is not a good use of the teacher’s time!

Research has also shown that, on average, only a relatively small percentage of a PE session is spent ‘on task’. In a review of studies quantifying ALT, Siedentop and Tannehill (2000) found that, as a percentage of total lesson time, ALT ranged from just 10% to 30% on average. Most of these studies use an observation tool called the ALT-PE, developed by Siedentop et al. (1982), which helps to categorise pupil behaviour. Give it a try yourself and see how your sessions compare to the research!

How do we maintain tempo?

So, like the DJ, we can see that it is important for a coach or teacher to have a good tempo to their session. Maintaining tempo maximises ALT whilst minimising opportunities for disruption. But how is it done?

First, there’s the issue of planning and structure. It’s important not to plan a session in ‘blocks’ of activity as the natural breaks between the blocks represent wasted time. There is no reason, for example, why session aims and outcomes cannot be communicated during a warm-up; and no reason the warm-up cannot evolve into an initial game activity, without a break in play. To the DJ this is just good mixing.

Second, it’s possible (and desirable) to instruct and feedback during an activity, rather than stopping it constantly. Even when stopping to ask questions, you can have participants work in small groups to solve problems and demonstrate to one another. Or, when working in pairs, participants should be encouraged to engage in observation, analysis and peer-coaching when inactive. This is still considered ALT. The challenge is to ask yourself at every turn: “could I find a way to instruct, feedback on, or change the activity without stopping it?”

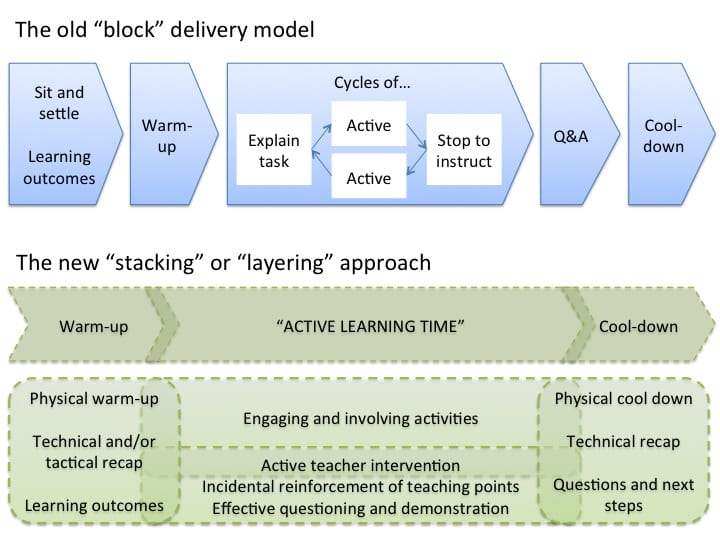

By way of illustration, the two models below represent two very different ways of structuring and delivering sessions. As you can see, the stacking/layering approach, though perhaps more challenging, would certainly have a better tempo with fewer breaks and much smoother transitions within and between learning activities.

Another point made in the research, however, is that ALT, in itself, is not sufficient for effective learning. Indeed, Lawrence and Whitehead (2010, p. 99) warn us not to focus too much on organisation and management, but to “see them as providing time and opportunity for effective teaching and learning to occur”. So, in order to increase the efficacy of ALT, ‘time on task’ is best coupled with particular instruction techniques and formats (Van der Mars, 2006). In particular, curriculum models such as Teaching Games for Understanding and Sport Education have been shown to be successful, as has peer tutoring. It is also important to set appropriately challenging tasks so that when ‘on task’, participants are engaged and not simply going through the motions.

These points are reinforced by recent guidance from Ofsted that details the characteristics of ‘outstanding’ teaching in PE (these guidelines also govern sessions delivered by coaches and came into force in 2012). I have abridged the rather long document in the table below and highlighted those points that illustrate the importance of providing opportunities for pupils to work independently and engage in peer-evaluation activities.

|

Outstanding teachers will… |

So that pupils can… |

|

|

|

Underpinned by an outstanding curriculum that… |

|

|

|

So, to put this all rather simply: those old, blocked sessions filled with stoppages and lengthy speeches simply won’t cut it anymore (at least not as far as Ofsted are concerned). We all need to start connecting with our inner DJs: delivering smooth and seamless sessions, packed with floor-filling activities and layered with incidental reinforcement, quality questions and peer tutoring. In this way we might all be able to get the next generation dancing to a different beat.

References

Lawrence, J. & Whitehead, M. (2010) Lesson organisation and management, in Capel, S. & Whitehead, M. (Eds.) Learning to teach physical education in the secondary school: a companion to school experience. London: Routledge.

Van der Mars, H. (2006) Time and learning in PE, in Kirk, D., O’Sullivan, M. & MacDonald, D. (Eds.) Handbook of physical education. London: Sage.

Siedentop, D. & Tannehill, D. (2000) Developing teaching skills in physical education. McGraw-Hill.